By Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine

Editors of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions

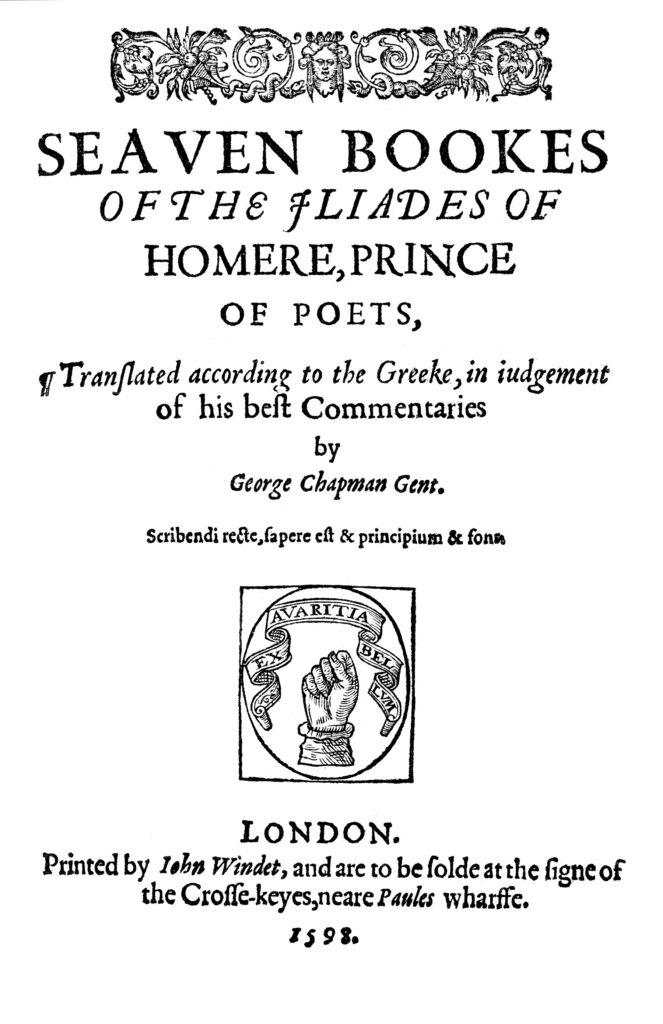

For the dramatic speech and action of Troilus and Cressida, Shakespeare turned to two of the most prominent authors in his culture. The first was Homer, who had inspired much of Greek and Latin literature as author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, the epic poems treating the Trojan War and its aftermath. The second was Geoffrey Chaucer, who, as author of The Canterbury Tales and the great romance of the Trojan War Troilus and Criseyde, was the only English writer granted status comparable to the titans of classical literature. Homer’s heroes, especially Achilles and Hector, are so magnificent that they attract the interest and intervention of the gods of the classical world. These gods contend with each other over the fates of their favorites, and sometimes even join the fight with them on the battlefield between the walls of Troy and the ships of the Greek invaders. The Greeks and the Trojans battle over Helen, the queen of Sparta and wife of Menelaus; she was taken from him by Paris, a son of Priam, king of Troy, and now is held within the city’s impenetrable gates and walls. Helen, every bit as magnificent as her male counterparts, is, in Homer, innocent of inconstancy because she is the victim of a divine spell.

Chaucer’s young Trojan prince Troilus and the widow Criseyde, with whom he falls in love, are fitting company for the Homeric heroes among whom Chaucer places them. However immature Troilus is at the beginning of the romance, his love for Criseyde matures him and ennobles his character, so that by the time they consummate their love, she can imagine him providing her the protection of a wall of steel. During their long affair, he loves her with great constancy. And he continues to love her after she is sent away by the Trojan council to the Greeks, to whom her father has already fled, and even after her betrayal of him when the Greek Diomedes prevails on her to accept him as her lover. While Criseyde turns out finally to be false, Chaucer and the rather clumsy and inexperienced narrator he creates both seem highly sympathetic to her in her vulnerable state. Up to the moment of her inconstancy, the poem is lavish in providing readers with details of her domestic situation and of her states of mind and feeling in a way that draws us close to her. Only Chaucer’s Pandarus and Diomedes seem to anticipate their Shakespearean counterparts, both men ruthless in exploiting Criseyde’s fears.

None of Shakespeare’s characters are the exemplars of heroism, constancy, or greatness found in Homer’s and Chaucer’s creations. In part, their diminishment in Shakespeare’s play may result from his transformation of them from epic and romance to drama. By convention in epic, the characters associate with the gods and thereby share the glory of these divinities; by convention in drama, the gods do not appear, and the characters therefore cannot exceed the limits of their humanity. By convention too in both romance and epic, the characters are presented to us by admiring narrators; by convention in drama, the characters must speak for themselves. But the shift in genre from epic and romance to drama cannot in itself account for the shrinking of the Homeric and Chaucerian characters to their Shakespearean size.

Instead, Shakespeare shapes the action of his play and the speeches of his characters so as to diminish the characters. The leaders of the Greek army, General Agamemnon and his councillors Nestor and Ulysses, talk endlessly as they scheme to get their chief warrior Achilles again to fight. Their schemes involve deception and cheap theatricality, and Greek officers and warriors alike are presented as fitting subjects for the cynical Thersites to lash mercilessly with his tongue. On the Trojan side, when the leaders meet to discuss whether to keep Helen, Hector provides powerfully reasonable arguments for delivering her up to the Greeks and then, on a seeming whim, sides with the others in continuing the war to keep her. In Shakespeare’s version, all the Greeks and Trojans, Paris excepted, doubt that Helen is worth the lives lost in their war for her. Just as Paris dotes on Helen, so Troilus on Cressida. Yet in contrast to Chaucer’s Troilus, Shakespeare’s fails to mature in response to his love and remains in adolescent self-absorption, almost indifferent to Cressida’s plight when she is forced out of Troy and made to go to her father in the Greek camp. For her part, Shakespeare’s Cressida shows nothing of the thoughtful reflection of her Chaucerian predecessor; it is replaced in her by calculation and manipulation of her suitors. Apparently, Shakespeare chose to part ways with Homer and Chaucer by throwing onto their characters a relentlessly satirical light, one that makes his play a savage attack on the ideals that serve as cover for greed, violence, and lust.

After you have read Troilus and Cressida, we invite you to turn to “Troilus and Cressida: A Modern Perspective,” written by Professor Jonathan Gil Harris of George Washington University.

From the Folger Library collection.